I was going through some old bookmarks the other day, when I found this entry by Wil Wheaton:

On January 28, 1986, I was home from school with the flu. I remember that, no matter what I did, I couldn’t get warm, so I was sitting in a hot bath when my mom knocked on the bathroom door.

“There was an accident with the space shuttle,” she said, in the same voice she used when she told me that my grandmother had died.

For the next few hours, I sat on the couch, wrapped up in as many blankets as we had, and watched one of the local news networks – probably CBS (our local station was an affiliate) – cover the unfolding disaster. Because of the fever and the years between now and then, I can’t recall a single detail other than how impossible the whole thing felt. How could something like that even happen? And did it mean that we’d never put people into space again?

It really hit me that of all the memories I have of high school (most of which have faded, and many of which are gone), I remember January 28, 1986 like it was yesterday.

I was in Mrs. Catto’s English class, fourth period, right after lunch. I’m not sure that she was lecturing; I remember a fair amount of discussion and chaos, probably because we were working on a writing assignment and were reading our rough drafts to each other. John G. came back into the room from a bathroom break and announced “The Space Shuttle blew up.”

Mrs. Catto chided him. “That’s not funny, John. You shouldn’t joke about things like that.”

“I’m not joking,” John protested. “I just came from Mr. Rex’s room, and his class was watching the shuttle launch and…it blew up.”

John and I were not friends (we were not enemies, either, but he was an athlete and his family had money and I was clumsy and my family didn’t have money, and so we just ran in different circles1) but there was something on his face that just seemed so pained that I couldn’t help but believe him.

I’m not sure how the rest of English class went, but my next class was American Government, which Mr. Rex taught. Surely I would get the details then.

This was, of course, 1986. The internet? Nobody had ever heard of it. Computers? Sure, some vague thing that some people might use at work, but only geeky people who are good at math might have one sitting on their dining room table. The height of technology in this small midwestern town in 1986 was cable television, and Mr. Rex, as the only social studies teacher for grades 7-12, was the only teacher who had it.

The mood was somber as we walked into Mr. Rex’s class. People who were talking or gossiping loudly suddenly became quiet when they walked in. Mr. Rex, generally a friendly, jovial fellow who never failed to greet us, sat silently at his desk, staring up at the television screen while the news (probably ABC, but who knows at this late hour?) tried desparately to come up with an explanation, and sadly realized it couldn’t even come up with the right questions.

School was different in those days. We didn’t try to cram as much information into kids as we do now, so we only had six classes in a day, and the classes were a good five or ten minutes longer than now as a result. So for almost an entire hour, all of us—25 or so students, and Mr. Rex—just sat there, watching this ancient television, trying to figure out how this could have happened. Every once in a while someone would start to ask a question like “But how could this even happen?” but they were quickly shushed by the rest of the class.

I grew up in a small town, but unlike what 1950s television (or 1960s or 1970s or even 1980s television) would have you believe, small towns are not all that uniform. Most of the kids in this class were white (or in my case, at least partially white), but some were the children of lawyers (John G.’s dad was a lawyer) or the children of uneducated factory workers, or the children of farm laborers, or the children of immigrants who had to translate for their parents, or the children of parents spending time in a crossbar hotel. Some of us had steak and baked potatoes for dinner every night and never worried about whether the electricity would stay on, and some of had macaroni and butter with salt and pepper for dinner every night, and worried about which bill (phone or electric) wouldn’t get paid that month.

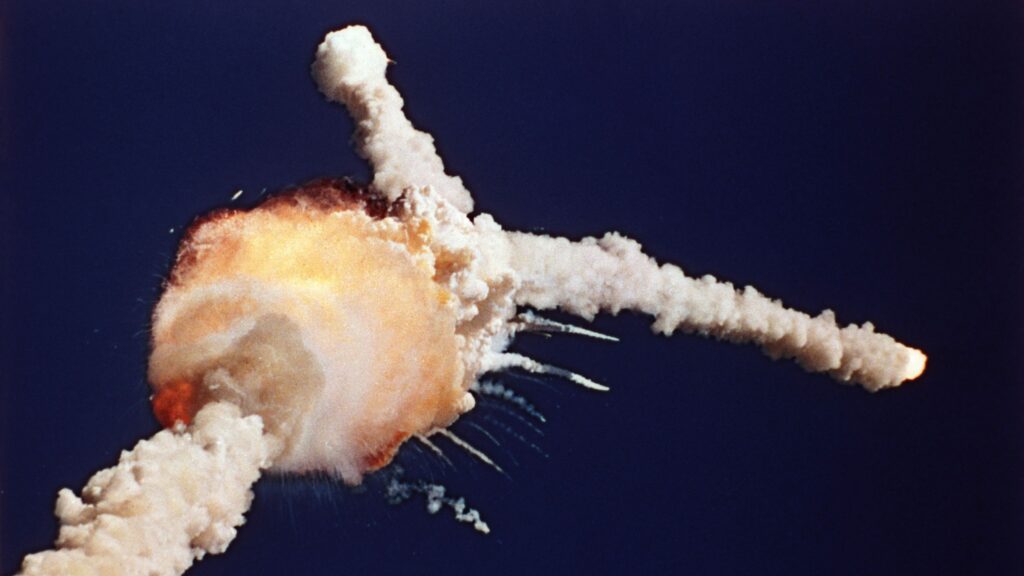

So…not a diverse community ethnically, but a diverse community economically. There was very little that all of us had in common other than being prisoners of a small midwestern town, but for that single 55 minute period, the one thing that we all did have in common was that we were all struck by the disaster that was the shuttlecraft Challenger exploding, with the loss of all on board.

Most of us had spent the last six or seven years hearing Ronald Reagan talk about how he was going to “make America great again” and how his presidency meant that it was once again “morning in America”. Our parents believed that, and our grandparents believed that, and our teachers believed that2 because this was a small town in middle America and conservative values tend to reign in such places.

We had taken so much pride in the shuttle program (this was something the Soviets had tried to get off the ground, but had failed miserably when Reagan decided to win the cold war by bankrupting them; sadly he also bankrupted us, both economically and morally), and yet here it was, blowing up in our faces in endless repeats on the newest technological miracle we had: cable television.

It was like all the promises that had been made to us just blew up in our faces. We were told that America could do anything, and yet we clearly couldn’t. We had defeated the British (twice!), the Mexicans, the South, the Spanish, the Germans (also twice!), the North Koreans (well, that one was a draw, but South Korea was intact, so we decided to call it a win), Viet Nam (well, we could have won that one, but the hippies and Black Panthers and also something, something Woodstock conspired against us), but we were beating the Russkies at their long-range ICBM game, and we had beaten some rank amateurs on a tiny little island called Grenada so that Reagan could still get a boner, so yeah, we do things! We win things! We’re America, god-damn it, and we get shit done!

Until, that is, a cold Tuesday in January.

It was like that carefully constructed house of cards had come tumbling down out of the sky only to smash into the ocean in a million pieces. This disaster meant that we were not miracle workers, we were not chosen by God, we were not destined to conquer the stars. It meant that we were fallible, that we could have hopes and dreams and that those hopes and dreams could come crashing down, if not around us, then on an almost endless repeat on cable network news.

Twenty four years later, Wil said this:

This morning, I sat in my office and watched the shuttle Atlantis launch into space via a NASA TV stream through VLC on a monitor that is bigger than my family’s 1986 television. When mission control gave the order to go with throttle up, I held my breath like I have every single time since the shuttle program was reinstated in 1988, and when the shuttle separated from the boosters and glided into orbit, I got something in my eye. Just take a moment, if you don’t mind, and think about what it means that we can leave our planet, even if we’ve “only” gotten as far as the dark side of the moon. Think about what it means that something as incredible as putting humans into space and bringing them back safely to Earth today earns less media attention and public excitement than the typical celebrity breakup.

What Wil got right here is the “bringing them back safely” part. Putting a person in space or on the moon, or on Mars, really isn’t all that difficult. A rocket is basically just a big gun, after all, and if there is anything that the United States understands, it’s big guns.

But it’s the “bringing them back safely” part that is the challenge. You can shoot someone off into space, but you can’t just shoot them back to Earth. You need a soft landing.

We are not good at soft landings. Soft landings are for wimps and sissies and people who can’t take it. This is America, by god, and we don’t worry about that kind of nonsense. If something bad happens to us, we just pull up our pants and get on with life.

Wil also said this:

We humans are a flawed species, to put it mildly, and I think we could do a much better job taking care of our planet and each other … but when I see what we’re capable of doing, it gives me hope that the future I pretended to live in twenty years ago will actually arrive some day.

We are definitely a flawed species. Our greatest flaw, perhaps, is that we prefer flash and style over substance, money and power over people’s lives.3 Sadly, most people view the Challenger disaster as a failure of science or of engineering. It wasn’t. The truth is that there were at least two engineers (Roger Boisjoly and Bob Ebeling) who had rung the warning bell at Morton Thiokol, saying that the temperatures that night and morning had been too cold (18°F/-8°C) for a successful launch because the rubber o-rings would not be able to seal the gap between the sections of the solid rocket boosters, potentially leading to an explosion. Ebeling’s daughter would later recall him saying “The Challenger‘s going to blow up. Everyone’s going to die”.4

Which is precisely what happened. But it didn’t have to. The reason NASA decided to press on with the launch had nothing to do with science, but with flash—Reagan was due to deliver the State of the Union address that evening, and boy, did he want to talk about the success of this program and also about putting the first teacher into space. The reason he wanted to talk about the success of the Shuttle program had nothing to do with scientific advancement. Even though the crew of the shuttle did a lot of scientific experiments on each mission which were talked about a lot in the news (as a young science geek, I was glued to the evening news when they were discussing these), the major purpose of the shuttle missions was to get satellites into space for private companies. It was as much or more about money as it was about science. Delaying a launch due to cold weather (“just put on a jacket!”) meant showing that this technology was not 100% reliable for business purposes. It meant that it had uncertainty, and one thing the business world doesn’t like is uncertainty. Therefore, face must be saved and money must be made and human lives be damned.

This is not unlike how most people view Jurassic Park. Most people tend to see it as a failure of science, and like to say “just because we can do it doesn’t mean we should do it”. But in Jurassic Park the science worked exactly as it was supposed to. It wasn’t the science that failed; it was the capitalism. The scientists said “if you make new dinosaurs, they will eat people” and the capitalists said “well, not a lot of people, and just imagine what it will do for ticket sales” and then what happened? The dinosaurs ate a bunch of people. Nearly the same damn thing happens in Jaws. Scientist and cop say “We need to shut the beaches down or people will get eaten” and the mayor “keep the beaches open, we like the money!” and then what happens? People get eaten.

If your business model involves people getting eaten, then your business model sucks.

But that’s most business models. If people aren’t getting eaten by dinosaurs or sharks, then they’re getting eaten by the machine that is really good but poorly delivered health care, or the machine that keeps kids from eating lunch at school because they can’t afford it, or the machine that means a very few people will get rich while a lot of people can barely keep their heads above water, then your business model sucks.

When I see what we’re capable of doing…

That’s a two-edged sword, isn’t it? Because the human race is capable of doing some absolutely wonderful things, and it’s also capable of doing some abominably awful things. But it seems to me that we much prefer to do the awful things, because it means we can be greedy and even turn greed into a virtue. We like to think that we are the smartest species on the planet, but we didn’t climb down out of the trees so we could walk on two legs and carry around an iPad. That’s not how evolution works. Our intelligence is just an accident of evolution, not the natural result of it. And that intelligence is killing the planet, because we prefer greed over taking care of each other. Jumping Jesus on a pogo stick, this is something that even parrots can get right, but we fail miserably at.

These are dark times, and they are definitely coloring how I view the world. Would I be feeling like this in 1100 or 1880 or 1933 or 1953 or 1968? Sure. Have I studied enough history to know that it is cyclical and that bad times come and go and we’re just in a very bad, very dark time right now? Sure.

But for the first time in human history, human greed has to potential to affect the climate in a way that would not be good for any of us.

So yeah, I’d like to look up at the stars and imagine that we, as a species, will get to that point where we can trek through the stars. But even in Star Trek, humanity had to go through a nuclear war to get to the point where they realized that not just could they do things better, but that they had to do things better. Will we learn those lessons? Or will we go out with a bang? Or with a whimper? Is our current situation just another blot on our history, or a tipping point toward an Earth where a single last human drags their thirsty body across a barren landscape before at last expiring at the edge of a drying pond?

I don’t know. I am pessimistic. (Not by nature, but by nurture.) But I’ve watched enough Star Trek to know that sometimes people have to be pushed to the very edge of a precipice before they achieve wisdom. Are we on the edge of a precipice? Not yet, but soon. Will we achieve wisdom? I have my doubts, but I also have my hopes.

Until then, I will keep looking up at the stars.

1I remember him being kind to me on several occasions, because of all the people in our sports-obsessed small town, he was one of two (Mr. Rex was the other) who seemed to understand that coordination, speed, and strength were a combination of both practice and gifts of nature, and that no one should be yelled at for being clumsy as long as they were trying. (And sometimes when I’m having a hard day, I think back to that day in fifth grade gym class when it seemed that everyone hated me and John G. yelled back at them “At least he’s trying!” I was then, and I am now.)

2Well, not Mrs. Catto, at least. She always had some pamphlets in her chalk tray about how MAD (Mutually Assured Destruction) was not a good idea, and others about how how nuclear power was not the answer. At least she put her money where her mouth was.

3There’s a reason the good aliens don’t visit us. If you’ve listened to my podcast, you know why.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.Permalink for this article:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.Permalink for this article:https://iswpw.net/2025/07/17/a-cold-tuesday-in-january/