“…He’s not a real person.”

“You’re only saying that to make me feel better.”

“Ok, he’s a real person. But he’s a different sort of real person.”

“In what way?”

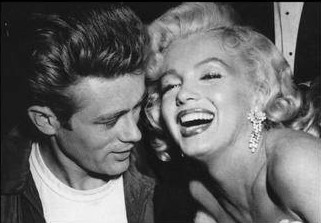

“I don’t know. He just is. He’s like James Dean and Marilyn Monroe and Jimi Hendrix and all those people. You know that he’s going to die, and it’ll be ok.”

Nick Hornby—About A Boy

It seems that every time someone brings up the death of a celebrity lately, someone else feels the need to mention that Betty White is still very much alive. In some ways, she is to the first fifteen years of the twenty-first century what Keith Richards was to the last fifteen years of the the twentieth century. Ever since the death of Marilyn Monroe, we mark eras and ages by the passing or non-passing of celebrities.

I am writing this just a few days after the death of Joan Rivers and less than a month after the death of Robin Williams. People are still reeling (in Williams’ case) and reacting (in Rivers’ case). I didn’t do much of either, to be honest. I just don’t feel that much about these events, and what I do feel, I don’t feel that strongly.

The earliest celebrity death I remember remembering is Elvis: I was a few years old, watching the television while my mother was cooking dinner. Walter Cronkhite announced that Elvis had died and I relayed that information to the kitchen by way of a shout, to which my mother (a diehard Elvis fan in those days) replied “What?” My age was still in the single digits then; it’s possible that a combination of YouTube and all the drugs I took in high school and college combined to create that memory. In any event, my mother has no recollection of it.

The last celebrity death I was truly shocked by was River Phoenix. Until then, the deaths of celebrities involved celebrities my parents liked and were similar to: they were old and had a sense of humor I would need to mature another generation to appreciate and share.

But River Phoenix was of my generation; if I felt young and strong and invulnerable, it only seemed right to imagine that celebrities my age were young and strong and invulnerable. As Stephen King has pointed out, teenagers are among the most conservative people on the face of the planet: they don’t like change, so they view themselves as invulnerable and incorruptible. They are incapable of seeing or experiencing the vicissitudes of age. It is only a news report about a senseless and meaningless death on a Halloween night that brought that mistaken point of view of mine crashing down to earth.

So while tweets about Robin Williams and Joan Rivers are still fresh, I just want to point out that I feel a whole lot of numb about their deaths.

Don’t get me wrong. It’s not that I don’t feel bad about their deaths. It’s just that I don’t feel bad in that way. It’s not that Robin Williams and Joan Rivers aren’t real people, it’s just that they’re a different sort of real person.

Let’s face it: 99.9+% of us never knew these people; never even had a chance of knowing them even if we had a chance of meeting them. Most of the tweets I saw about Robin Williams were about how his death affected the tweeter; I saw only a handful that mentioned his friends and family—the people who really did know him.

I’m not outraged by this, particularly. We live in a postmodern age where meaning is where you find it. For some people, to have arrived means that the number of followers they have on Twitter is higher than their credit score.

Do I feel bad for their families? Sure, I do, but only because I’ve seen images of them on television or in magazines or on the internet. But I don’t feel bad for them in the same way I feel bad for the families of people who have died and whom I knew in real life. I’m not going to make a casserole and send it over to Mrs. Williams or Melissa Rivers. I can help real people grieve; I can’t help people grieve whom I don’t know and who certainly have never heard of me.

The sadness of this age is that it’s easier to feel connected to the people you see on the television or on the internet than to the people who live across the street. When I was a kid, I knew the names of every household on my street. I was fuzzy on first names (especially with adults) but I knew if you were Mr. Jones or Mr. Smith, and I knew if your family was having problems.

No so anymore. For the most part, I don’t know any of my neighbors—I know the names of only a few, but I don’t know where any of them work, or the names of their kids or spouses, or whether they’ve recently suffered a death in the family. I don’t like this, and I’m pretty certain (if only because I’m an optimist) that they don’t like it either, but oddly enough, we can all live with the situation. We’ve managed to make our peace with it.

I have my reasons for not really wanting to know them (I’m pretty sure one of them is a meth dealer, for example), and I’m fairly certain most of them have theirs. Interactions consist of a not-so friendly wave or a not-so casual nod of the head. Most of my neighbors were not my neighbors five years ago; 70% of them live in homes that were foreclosed on or sold cheap, in a hurry and probably at a loss, as their occupants tried to stay one step ahead of the bank. (In this day and age, it’s hard to imagine anyone with a mortgage as an “owner”—at best, we’re all just occupants.)

So it’s no surprise that we know more about the lives of celebrities than we do about our next-door neighbors. We once put celebrities on a pedestal, and while we once fantasized about getting up there on the pedestal with them, the internet and 24/7 “news” coverage brings them down to our level. We used to wonder what John, Paul, George, and Ringo ate for breakfast; these days you can just check your favorite celebrity’s Instagram account to see pictures of their lactose-free, gluten-free, organic, vegan fair-trade breakfast.

When celebrities post such intimate details of their lives online, it’s hard not to feel that we know them. When our real neighbors shutter themselves inside, when our homes become fortresses of solitude, when we reach out electronically more than we do physically, we know we’re not in Kansas anymore, but we seem to prefer Oz anyway. Don’t make me face real life, let me spend all my time inside the Oasis*. The only question left is not whether we’re going to do anything about it, but whether we can do anything about it.

So while I feel bad that Robin Williams killed himself (a fact I learned about, incidentally, on Twitter), I’m not going to miss him. I didn’t know him. I’ll miss seeing new work from him, sure, but I won’t miss him personally. I won’t miss Joan Rivers, either, who was witty, self-deprecating, and highly intelligent (see her early work for her best examples), but was reduced by our short attention spans to a plastic-faced red carpet harpy, braying for our attention. In some ways, she died long ago.

All this saddens me terribly. I’m not sure which saddens me more—the fact that celebrities are more real to most people than the real non-famous people around them, or the fact that we are okay with it. At some point the real and the virtual have exchanged places, and it happened so smoothly, so under our individual and collective radars, that we haven’t bothered to raise a fuss. We could, but there’s always a celebrity drinking a mango smoothie that we need to retweet.

*Read Ready Player One by Ernest Cline if you don’t get the reference.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.Permalink for this article:

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.Permalink for this article:https://iswpw.net/2014/09/14/a-different-sort-of-real-person/